Between 1920 and 1939 Kaunas, or Kovno as it is known in Jewish culture, was home to approximately 40,000 Jews—about a quarter of the then Lithuanian capital's population. On the 22nd of June, 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, which had annexed Lithuania a year prior, and captured Kaunas two days later. By July that year German Einsatzgruppen and their Lithuanian auxilliaries had begun systematic massacres at the Tsar-era forts around the city, culminating in the so-called Great Action of the 29th of October, 1941, when almost 10,000 people were shot to death at the Ninth Fort in a single day. Within six months of the German occupation half the Jewish population of Kaunas had been killed. At the same time, the Nazi occupiers, along with members of the Lithuanian Provisional Government before it was disbanded in August, 1941, moved to establish a ghetto in the city's Slobodka district. When the gates were sealed on 15 August, 29,000 people were incarcerated there. Of the detainees who evaded death in those early months, most were used as forced labour for the Germany military, deported to other concentration camps, or perished some other way. The ghetto was destroyed three weeks before the Red Army was to arrive and occupy Kaunas in August, 1944. Few Jews survived to be liberated.

Decades later, in 2013, International Centre of Litvak Photography creative director Richard Schofield was scouring the archive at Sugihara House in Kaunas when he came upon a collection of photographs that had been smuggled out of the ghetto and entrusted to a non-Jewish family. Immediately he set about discovering the identity of the people in the pictures and tracking down their relatives, who turned out to include two prominent scholars of Yiddish in the United States. Schofield is still astonished by the rare find. “Getting photos out of the ghetto was not an easy job, very risky,” he told the Lithuania Tribune. “We now know from the relatives why they risked so much. It's because they knew they were going to die,” he said.

Meanwhile, Schofield, a British national who has lived in Lithuania for fifteen years, had set his sights on a dilapidated synagogue in the southeastern suburbs of Kaunas. Originally constructed in 1932, the unprepossessing red brick edifice was converted into a bakery in the Soviet era and now stands crumbling and overgrown with weeds. Little is known about the pre-War usage of the building. “We've found nothing except the architect's drawings. We don't know who the rabbis were, we don't know who came here,” Schofield said. He finds the lack of attention paid to the former place of worship disappointing. “Kaunas likes to talk about its rich interwar architectural heritage,” yet this “beautiful building with a rich history that could be being used for interesting, creative and educational purposes is being kept empty” by its owner the Lithuanian state, he said.

The IC4LP, which Schofield founded, is pushing to buy the building and transform it into a centre of Jewish cultural remembrance. He is confident the Lithuanian Government will cooperate eventually, but at present, he says, “the stumbling block is the price.” Schofield wants to pay just one euro, citing precedents around the world in which governments have handed over buildings of Jewish significance to community-oriented NGOs.

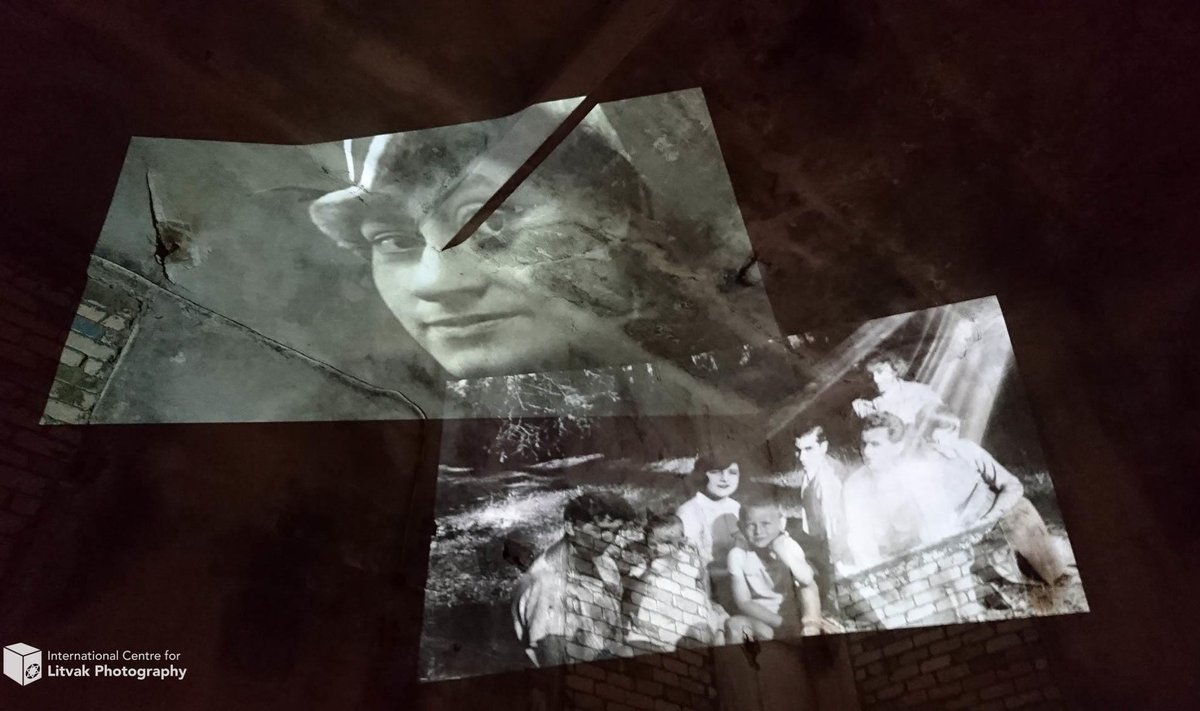

The abandoned synagogue is the setting of this week's commemoration program, which ties together the campaign to reclaim the building with the photographic discovery, as well as marking seventy-five years since 1941. Until National Memorial Day for the Genocide of Lithuanian Jews on Friday the public can visit the site and contemplate an artwork Schofield has installed inside featuring projections of the said photographs upon the walls of what was once the prayer hall and printed copies nailed to old wooden palettes in adjoining rooms.

Visitors will be able to hear the first portion of a seventy-five-year-long musical composition inspired in part by the story of the original owner of the photographs, Anna Varšavskienė. Before her untimely demise, Varšavskienė had had a notable career as a singer, performing regularly on the radio and in theatres. One extra document she attached to the bundle of photographs for safe keeping was a concert program. Moved by this, Schofield decided a musical memorialisation was needed. That task fell to Kiev-based composer Anton Dehtiarov, a church organist-turned-dance music producer whom Schofield had met working on a documentary project about the 2014 Maidan crisis in Ukraine. Together they developed the idea of creating a three “movement” mega-work: the first being the live electronic-ambient score that will fill the New Šančiai syngagogue for several hours a day each day this week; the second being three years of silence, reflecting the duration of Kovno ghetto's existence; and the third a computer-generated musical automation that will continue for the remaining 75 years, although how this gargantuan proposition will be delivered remains unclear.

Dehtiarov describes the project, titled The Kaunas Requiem, as a “mad and brilliant idea” that speaks to his deep interest in the history and art of the first half of the twentieth century. In the first movement Dehtiarov has aimed to create “a kind of ambient neoclassical style,” referring to one of the predominant pan-European musical currents of that era. In addition to improvisation on synthesisers and a live cello on at least one evening this week, he has incorporated recorded samples of Yiddish songs performed by Varšavskienė's sister, also a singer, thereby linking the composition to the photographs. Having himself lived through a political crisis of historic significance Dehtiarov feels empathy for the suffering of the Varšavskis family. “Maidan affected people deeply in Ukraine,” he said. “People were made to understand that you only have one life, so you must do the things that make you happy.” The experience impelled him to “talk about some higher things, some bigger things” in his art, which he believes he has been able to do in the Kaunas Requiem.

Ultimately, the Kaunas Requiem, the synagogue, the photographs, and the IC4LP's various other endeavours are components of “one big memory project” to honour the lost Jewish culture of Lithuania, Schofield says. He points out that “there's no Jewish museum in Kaunas,” adding his opinion that Jewish history is “not taught very well in school” either. That will change over time, he says, because the younger generation is already “listening much more than their elders.” And he is optimistic the open-mindedness of Lithuania's youth will flow to the IC4LP's ambitious undertakings: “with their brilliant ideas and creativity what we do will become part of the community, not just That Jewish Place.”