It is now 25 years ago since Soviet troops stormed peaceful protesters surrounding the TV Tower in Vilnius, resulting in 14 deaths. It was then that Lithuania made clear its will to be independent once again to the world. With a landmark commemoration this year, Lithuanians all over the world will stand by their values and culture with as much conviction as they did a quarter of a century ago. How did people then experience the events, and what has changed since?

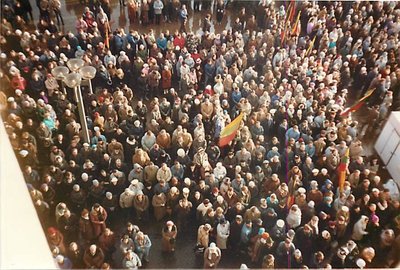

It was January 13, 1991, when the pressure cooker that was the Soviet Union reached its boiling point. On that day, now dubbed Freedom Defenders’ Day, the tensions that had risen with the Act of the Re-Establishment of the State of Lithuania, adopted by the Supreme Council almost a year before, came to a violent conclusion. Standing in unison against the Soviets, Lithuanians who feared intervention from Moscow gathered in peaceful protests around their key buildings to protect them. The world watched as 13 protesters were killed and hundreds wounded at the Vilnius TV Tower.

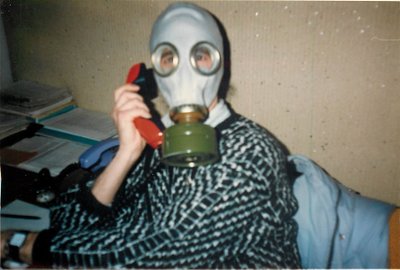

Linas Muliolis, a Lithuanian-American, who was in the parliament building in Vilnius that January after volunteering to work as an interpreter, remembers those days well. As thousands of Lithuanians stood arm in arm around the parliament protecting it against a feared Soviet take-over, the-then 20-year-old Muliolis was talking to the foreign press and working as an interpreter. “Everyone was scared,” he said.

Everyone old enough to remember will recall with clarity their own version of the events leading up to the violence of January 13. Throughout Lithuania church bells rang, calling up people to central points in their cities and towns to be driven en masse to Vilnius.

When the Soviets started reclaiming key buildings one by one, Muliolis who was there to hear all the reports coming in, did not sleep in a 108-hour span. Instead he, as others in the parliament, were preoccupied with getting these reports out to news media all over the world. All the while protesters outside were singing folk songs, remaining unmoved despite the biting cold.

As protests errupted throughout satellite Soviet states, support came from émigré communities all over the world. Numerous Lithuanians in the US supported the protests from afar, raising awareness in their own country. With the passing of years this sense of solidarity for the small and often overlooked European country has not ceased.

Rima Gungor, a young American director of Lithuanian decent, is just now finishing up Game Changer, a documentary about the Soviet occupation and the widespread tumult around the January events.

“The one thing that is extremely unique about the Lithuanian freedom movement is that it was literally global,” Gungor said.

Oppression and patriotism

The Lithuanian people have faced much oppression throughout their history. This, perhaps, can be seen as one of the main reasons for its people’s strong sense of patriotism. Gungor who grew up in Chicago, which has one of the largest Lithuanian communities outside of Lithuania, was taught her whole life that preservation of her heritage was important.

Muliolis tells a similar story. Under Soviet occupation the tricolor flag and Lithuanian meetings were forbidden, he and his fellow young Lithuanian counterparts in the United States were told that their culture should be persevered. In case, he was told, it would be forgotten or lost in the occupied country itself.

Culture is still seen as a highly valued good in Lithuania today, not just at the many traditional restaurants and folklore dances but in the country’s schools. The January events are part of all school curricula. At the start of each year, teachers talk to pupils about the implications of the 1991 events. At Sausio 13-osios mokykla elementary school, this week is dedicated to teaching the children about Lithuania’s freedom movement.

“It is important that the children learn about these events, because now we can travel, do what we want, and speak our minds,” said Ieva Jasponytė, vice-principal at the school.

Attention to the January events crosses all age groups with several commemoration events organized every year. One of them is an international run called the “Road of Life and Death”. The run, that was first organised in 1992, has a growing number of people joining in every year.

The run starts at the cemetery where most of the TV Tower victims are buried and finishes at the TV Tower itself. Twenty-four-year-old Jonas Vadapalas ran for the second time this year: “Even though I wasn’t alive during the time, it feels like being part of my own history as well.”

Vadapalas recalls how surprised he was to see mostly people in their twenties and thirties, who did not witness the January events, join in for the race. To Vadapalas, a project manager at Create for Lithuania, the January 13 events show that for the people of Lithuania their values, country and freedom stand above even their own lives.

Images became symbols of independence

The images of the January events are many, graphic, and easy to find. As time went by, pictures and videos of the violence have grown to be interlinked with Lithuania’s identity. Those who were there, however, don’t need the footage to remember. The images are seared into their minds.

Muliolis remembers a distressing radio report coming in on the night after the Soviet troops took over the TV Tower. They were coming.

“I looked across the river and saw tanks come racing over the bridge. My heart dropped through my stomach. What I saw then was a mass of people running right up to the intersection to shield it off from the tanks. I don’t know how the tanks turned at that speed, but they did. I’ve never seen such bravery again.”

Now the images of the January events, suddenly, are filled with symbolic heaviness. With the Russian annexation of the Crimea, and conscription reinstated in Lithuania the values that once made Lithuanians stand in defence of their country’s freedom now surface again.

“It is heartening to see how Lithuania stands by Ukraine. Sometimes I fear for Lithuania. But luckily we are part of NATO,” said Muliolis.

Gungor believes history is now repeating itself and Game Changer is coming out at a time when interest from the international community will be strong.

Lithuanian historian Dr Vladas Sirutavičius points out that even though the situation in Ukraine is different from Lithuania’s own struggles 25 years ago, it is important to see that only peaceful methods can create positive political outcomes.

“We must use more diplomacy. It will make for more safe and secure surroundings. Not just for Lithuania, but generally in Europe too,” said Sirutavičius.

History is never simple. It is multifaceted, and recent history is even harder to grasp in its full complexity.

“History always has both a bright and a dark side. Yes, it was a drama that enveloped at the TV Tower, but we were also shown one very crucial thing. Solidarity is important,” Sirutavičius said.

This solidarity showed up in many unexpected places. “It is important to stress that not only here in Lithuania the feeling of solidarity was strong. In other countries, even in Russia itself, solidarity with Lithuania was expressed. Huge gatherings and meetings were held in Moscow and Leningrad. There were even some Russian journalists who covered the events objectively and sincerely,” said Sirutavičius.

Muliolis, who could pick up a medal for his service to the country, is positive about Lithuania’s future. “I know I played my part 25 years ago. I am sure Lithuania will be ok now.”

The January events will be remembered as one of the archetypes of peaceful protest movements. If one thing is clear in the geopolitical climate of today, it is that the Lithuanian people worldwide stand in solidarity now as they did then. They will not forget what happened in January 1991.